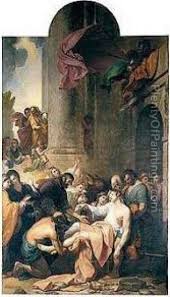

| A painting by Benjamin West titled “Devout Men Taking the Body of St Stephen” was commissioned in 1776 by Reverend Thomas Wilson (b. 1703 – d. 1784), Rector of St. Stephen Walbrook, and given to the church for installation over the altar on the east wall. |

Devout Men Taking the Body of St Stephen

Benjamin West PRA (October 10, 1738 – March 11, 1820) was an Anglo-American painter of historical scenes around and after the time of the American War of Independence and the Seven Years’ War. He was the second president of the Royal Academy in London, serving from 1792 to 1805 and 1806 to 1820. He was offered a knighthood by the British Crown, but declined it, believing that he should instead be made a peer. He said that “Art is the representation of human beauty, ideally perfect in design, graceful and noble in attitude”.

the Benjamin West painting on the East wall

A painting by Benjamin West titled “Devout Men Taking the Body of St Stephen” was commissioned in 1776 by Reverend Thomas Wilson (b. 1703 – d. 1784), Rector of St. Stephen Walbrook, and given to the church for installation over the altar on the east wall.

By 1848 it had been removed from the east wall and re-installed on the north wall of the church. In 1987 it was removed from the church and placed into storage. On July 10, 2013, the Consistory Court of the Diocese of London granted St. Stephen Walbrook faculty permission to dispose of the Benjamin West painting by sale. The Arts Council of England subsequently granted an export license for the work on March 19, 2014, at which time it was sold to a private American collection. In 2015 the painting was gifted anonymously to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in honour of Malcolm Rogers to celebrate his twenty years of extraordinary leadership as Director of the MFA.

Read more

The painting was not in good condition by 1814, and the artist undertook the cleaning and varnishing of it. By 1848, the painting had been taken down, and moved to the north wall. The church was the subject of reordering during the period 1978 to 1987, at which time the painting was removed to storage. The main reasons why the petitioners applied for a faculty for the disposal of the painting were that it would not be appropriate to reintroduce it; that the church needed financial resources; and that the picture had been identified as the most appropriate asset to realise. Having heard evidence from both sides, the Chancellor concluded that, on the balance of probabilities, the picture was introduced into the church without a faculty, and that its introduction compromised the integrity of the Wren building in scale and visual appearance, and by the damage to the original fabric in taking out and bricking up of the east window.

The evidence established, the Chancellor said, that Dr Wilson commissioned the work to hang above the altar, and that West painted it to hang there. So not only did the painting compromise the Wren concept, but the painting was compromised when it was moved to the north wall just 45 years after it had been cleaned and restored by the artist. That move, the Chancellor found, was because the worshipping community did not want it where it had been installed, or at all, but they did not feel that they could get rid of it altogether. The Chancellor also said that, “whatever the merits of this painting, or Benjamin West as an artist”, he had “a higher reputation and profile in the United States of America than he does in the United Kingdom, although he . . . did virtually all of his painting in Europe”.

As a matter of law, the Chancellor said that he had no power to order the return of the painting either to a specific location, or to the church generally, although, if he expressed an opinion to that effect, the petitioners would be morally or honourably bound to return the painting into the church. The petitioners’ evidence was that, because of the nature of the reordering, the return of the painting would have a negative impact both on the appearance and layout of the church and its worship, in particular the eucharist, as the central altar brought things together under a central dome. It was said on behalf of the CBC that the parish should not be allowed to “get away” with the illegal act of removing the painting from the church. The Chancellor said that, while he understood why the CBC might think that way, it was nevertheless “an unattractive way of thinking”.

These petitioners had behaved entirely properly in regard to the painting, the Chancellor said. The current parishioners were the “double victims of the high-handed and unlawful behaviour of previous incumbents”. This case was an object lesson of “[former] incumbents’ behaving as though the church building was a sort of personal doll’s house for them to play with”, without reference to the parishioners or the authority of the Chancellor. Unfortunately, the Chancellor said, that attitude was not restricted to previous centuries, but was “still held by certain incumbents today”. Eventually, as in this case, however, “the pigeons come home to roost, and subsequent generations have to bear the consequences and meet the costs. The original introduction of the painting was to the detriment of the interior of the church, the Chancellor ruled, and its reintroduction would be, too.

Read less